Wednesday 8 May: Parhelia (Sun dogs), halos and solar pillars

I woke up at 07:15 after a reasonable sleep… at least once I had put ear plugs in, thanks to my snoring tent mate and the constant flapping of the tent in the wind.

I wore two pairs of long johns, a summer singlet and a winter singlet, a pair of long thick woollen socks and a spare pair of boot inners to bed and of course a sleeping bag liner. During the night I put on an extra top.

My toes were still a little on the cold side for some of the night, despite the temperature not being as cold as last night; my sleeping bag is definitely not rated for -40 °C. Last night I hung a data logger from the roof of the tent; the log file is ‘in tent night of 7th May 2013.pdf’; note that the time scale is Sydney time so just subtract 12 hours. You can see quite clearly when I left the Big House at 23:30 pm, when I entered it again at 07:30 and when I went back outside again shortly afterwards. You can also see how the humidity went up inside the tent from our breathing.

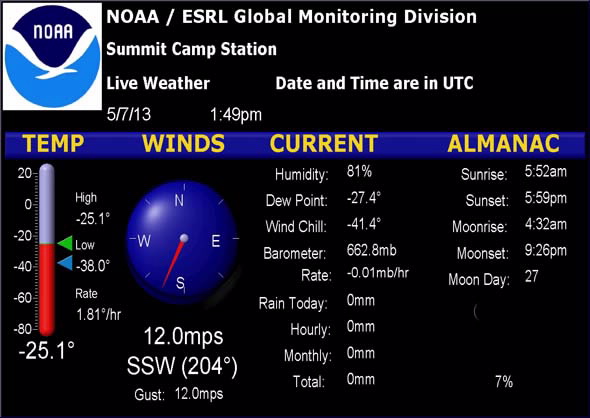

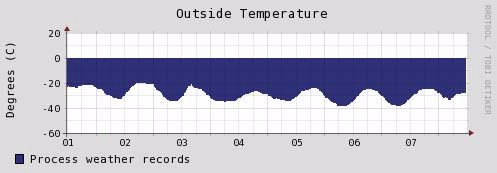

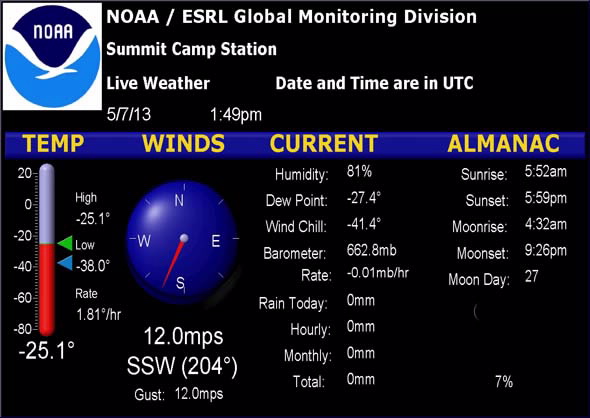

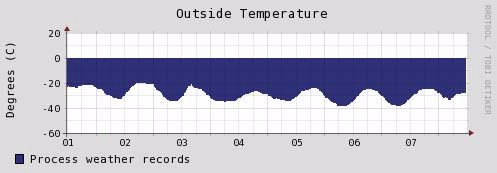

The lowest temperature was -18.5 °C. I also saved the Summit temperature record (the images you can view below) and you can see the lowest temperature was about -34 °C, about 4 °C warmer than last night. So we seem to be about 16 °C warmer in the tent, thanks to our combined body heat. They call these tents ‘Polar Ovens’ for a good reason! As per usual, everyone assembles in the Big House for the Station Leader briefing.

|

| Summit weather as at 8 May, 2013 from ESRL in Greenland |

|

| Summit weather as at 8 May, 2013 |

It will be a busy day, with a Bassler aircraft from Kangerlussuaq scheduled to land at 10:15, followed by a Hercules C130 at 13:45, along with the continued deployment of our camp.

Aircraft take priority, and it looks to me as though we will be spending another night here. It is difficult to work out where everything is, despite the Cargo Tracking System (CTS).

All the gear must firstly come through Kangerlussuaq where it awaits a flight to Summit. Some gear arrived on flights before us, some on our flight and some will come on following flights, including this afternoon’s.

Once at Summit it goes into storage until it can be taken out to the camp site, so it is really important to know what is there and what is here and what is still to arrive, which is quite tricky in practice, especially as it is generally ‘palletised’, meaning it is stacked in and almost two metre cube and can’t be easily inspected. Everyone must also keep be very careful with their personal gear, especially while we are ‘in transit’ at Summit; there is plenty of opportunity to misplace things and that can be disastrous. Such is scientific expeditioning in Polar Regions.

We have had a few power outages at Summit due to the additional power drain the extra inhabitants have generated. It seems that our camp setup is quite well advanced.

The big omissions are the science shelter, the heating system, a few sleeping tents, the toilet tent, frozen and DNF (do not freeze) food and various other items. …. a pause as I was summoned outside to undergo skidoo (aka snowmobile) training. Strangely, in my three previous trips to Antarctica somehow I never travelled by skidoo, either as a driver or passenger. Man, that was serious fun! Also a good chance to check out the GoPro mounted on the front of the skidoo.

It is really important to know how to drive these machines as they will be the way we commute between Summit Station and our Science Camp, some 10 km to the NW. We will have three skidoos, one 4 stroke and two 2 stroke, along with sleds behind. Two people can ride on the skidoo and passengers and supplies on the sleds.

Back inside the Big House at 11:50, the word is that the Basler hasn’t ‘off-decked’ yet and the weather window is closing. It is now -23 °C with 22 km winds blowing from the SW. Visibility is about half a kilometre and seems to be getting worse with the drifting snow. This could affect not only the aircraft flights but also the final setup of our camp.

This is called the A-factor.

OK, it is 21:50 and I’ve just had dinner at the Big House after our team returned from the drilling camp. Once we got word that that all flights from Kangerlussuaq were cancelled for the day the decision was taken to make the trip out to camp. One really pressing issue is to check our inventory, which is really quite large. We really needed to eyeball the equipment and supplies that had actually made it to the camp and work out what was missing.

All scrambled to get ready, which involved putting on all of our extreme weather gear for the traverse. Once ready, we assembled in the Big House to check that all three GPS had all the necessary waypoints loaded, that we had three working VHS radios, that we had two Iridium satellite telephones with speed dial back to the Summit command centre and that we had a working Personal Location Beacon (PLB). The Station Leader also needed to know our Iridium telephone numbers and that all the equipment actually worked.

All this took some time, and of course some of the equipment didn’t work and had to be replaced. Then we were off: three skidoos, two with Nansen sleds behind (one loaded with our frozen food stores) and a Tucker: a large tracked vehicle with a cabin. We got as far as the taxi way for the ski way when it was clear there were problems with the skidoo I was riding pillion on. We returned it to the Science and Operations Barn (SOB), hitched the sled to one of the others, and I jumped on a Nansen sled, with a Go Pro in my hand.

As I write it has turned midnight and we need to be ready for a possible 08:30 start to camp; if so this is my last opportunity until we return to upload this dispatch and some photos so I will cut it short. Suffice it to say, we had a really productive few hours at camp getting everything organised and working out what’s missing.

The main items yet to arrive from Kangerlussuaq are my ice core boxes and the Blue Ice Drill (BID); these are expected on the first Hercules flight; there are two scheduled for tomorrow: one at 10:15 and the next 11:45.

We hope to get off to camp before the pandemonium of C130 arrivals begins. We also have to transport the science lab out there by sled. Anon. Oh, one thing I should mention is that we have been treated to some wonderful optical effects in the sky as it filed with ‘diamond dust’. Parhelia (Sun dogs), halos, solar pillars etc.

Tuesday, 7 May: Cold – 1 vs technology - 1

Well, looks like I survived last night. It was so cold that my Swiss Army watch stopped working at 01:36.

When I got up it had started again, but had lost three hours. On the plus side, my iPad worked fine at these temperatures. It was lightly snowing inside the tent all night; our breath condensed and froze on the walls of the tent and the wind shook the fine ice particles off to drift gently over us. It was bitterly cold making the ~ 100 m trip from tents to Big House, with a 14 knot wind and -34 °C.

Time to get the balaclava out. There was a briefing by the Station Leader and amongst other things he told us that the weather conditions were very marginal for the continued deployment of our camp; no surprise there. The drifting snow is making visibility very poor and the wind chill factor is quite extreme; the wind is picking up and is now 20 knots. I rather suspect we will be staying here again tonight. I shall be wearing an extra pair of socks in my tent tonight!

We spent the day organising food.

Monday 6 May: ‘Almost’ a summer day on arrival at the Summit of Greenland

It is 20:00 and I am sitting in ‘The Big House’ in the Summit Station; it is -29 °C outside and a 14 knot wind is blowing outside. You guessed right: I am on the Summit of Greenland, at 3216 masl!

Things went well this morning and we took to the air at 09:30. As there were only 15 passengers, the seat configuration inside the hold was different for this flight and we could all stretch out our legs. I was quite surprised when I felt the skis touch the snow surface at 11:20 as I though the flight would be longer. The temperature was about -24 °C, the sun was shining and the wind was gentle… almost a summer day! The snow was squeaky underfoot which is always a good sign.

It felt fantastic to finally arrive and we were all in great spirits. The locals gave us a warm welcome and we followed them into The Big House, which is the kitchen, dining room, lounging area and generally the hub of Summit Station. It is mounted about 4m above the snow surface so the drifting snow passes underneath and doesn’t build up blizz trails. It is a warm and convivial and the cook, Sarah, is highly regarded and hasn’t disappointed so far.

While everyone settled down inside I went back out to watch and film the C130 taking off for the return trip to Kangerlussuaq. Firstly they had to unload the large pallets through the rear cargo door, then load others back in for the return journey. This took some time and I was glad the wind was low as I had fairly light clothing on. I then watched with interest as the plane went up and down the snow runway a few times but still didn’t take off. Then I noticed the rear door open again, the plane lunged forward and a large pallet slid out the back and onto the snow. The door closed again, the plane taxied to the end of the runway and finally took off, an impressive sight with the huge plume of snow thrown up behind. Apparently the load was too heavy for the remaining fuel on board so they dumped the pallet for another flight, a not-uncommon occurrence. By this time I needed to seek out the warmth inside.

Next was lunch and then briefings by the Station Leader and Doctor. High altitude sickness is a real possibility for us new arrivals, having ascended to 3216 m from sea level in under 2 hours. We were warned not to exert ourselves for the next 24 hours, to drink lots of fluids and to expect headaches and nausea. Great. Not sure what’s worse: the headaches and nausea or drinking lots of fluid before going to sleep in a tent at -30 °C. Glad I brought my piss bottle with me!

Next, luggage was checked, plans made for sourcing food for our camp from the kitchen stores plus numerous other organisational tasks. About 17:00 we were told our personal luggage was ready so we collected it and headed over to our designated tent in ‘tent city’, and array of 4 x 6 tents, each big enough to sleep 2 people. It was important to spread out our sleeping bags well before sleeping so the down could loft and provide the best insulation. Tonight will be an interesting one for me: I have never used this sleeping bag before and I see it is now -31 °C, having dropped 2 °C in an hour, or so. Best to find out how it performs here where I can retreat to a warm building, rather than in our camp.

So far, I am feeling fine. I could certainly notice the lack of oxygen at this elevation on arriving; the air pressure is so low here that water boils at 89 °C. Although feeling a little strange from time to time during the day, I have not had any headaches or nausea so far and I haven’t needed any preventative medication. Let’s see what tomorrow brings!

Sunday 5 May: Andrew explains the team's research objectives

Woke up at 07:30, showed and dressed in warm gear and dumped my two large duffel bags of gear, each ~ 22 kg, into the back of the truck along with the others. This gear has to be stowed in pallets again for the C130 trip to Summit. Then we headed off with our meal vouchers to the ‘canteen’ attached to one of the hotels, about a mile’s walk away. The morning was sunny but fresh: about -5°C.

We bumped into one of the KISS people who told us that weather conditions on Summit were not good and the flight was on hold, with the window open until 18:00. The A-factor had struck! This was confirmed when we got back to KISS, with the report that 18 knot winds blowing across the runway and drifting snow were making landing conditions bad.

By lunchtime the cancellation of today’s flight was confirmed and we headed across to the Polar Bear for lunch. I did some shopping, had a bit of a look around and got the usual tasks underway: managing photos on four devices: video camera, GoPro, mobile phone and Nikon SLR, organising files and writing this diary.

We have since been informed that tomorrow there will be a bag run at 06:00, transport for breakfast at 07:00 and that we should be dressed and ready to fly by 08:30. This means having all cold weather survival gear on in case the plane has to ditch along the way. In a way it has been good having a fairly relaxed day in which to get organised after the long trip from Sydney and to get to know the other eight people who will share our camp. Hopefully we will get up onto Summit tomorrow. Temperatures there have been -40 °C to -30 °C at ‘night’ and -30 °C to -20 °C during the day. It will become warmer and the brief twilight will go while we are there and we move into summer.

After writing the above, our nine-member field party met to discuss the scientific goals and the logistics of how they were to be accomplished. In a nut shell, the principal goal is to study the fate of in situ produced 14C (‘radiocarbon’) in firn and shallow ice. This firn air will be used for other studies as well, for example analysis of the isotopes of neon.

Secondary goals include a detailed analysis of the bubble-close off process as the firn becomes ice, analysis of last season’s anomalous melt-layer (specifically the effect it had upon CH4 (methane) concentrations), measurement of black carbon aerosols over the last 200 years and also of the 10Be (beryllium-10) concentration over the same period. I am involved in the primary goal, through measurement of the 14C concentration of the CO (carbon monoxide), CO2 (carbon dioxide) and CH4 by AMS (accelerator mass spectrometry) in our laboratory at ANSTO in Southern Sydney. I am also involved in the latter two secondary goals and a ~ 85 m core from the surface will be shipped back to Australia for these studies.

Some of these terms deserve an explanation. As snow falls in Polar Regions it generally doesn’t melt, the big melt all over Greenland last July was unusual, but not totally unprecedented. So, the snow continues to build up, compressing and sintering the underlying snow. While this process is going on, the spaces between the snow crystals which are filled with air are still in contact with the atmosphere, but through paths of increasing tortuosity as the depth beneath the surface increases. We call this sintering snow ‘firn’ and at Summit the firn layer is about 65 m thick. At about this point, the ‘lock-in depth’, these channels begin to close off and the atmospheric air within is locked into bubbles that then move with the ice.

Of course this air will contain CO, CO2 and CH4 in very small concentrations, just as the atmosphere does. The C (carbon) atoms in these molecules can be one of three carbon isotopes: 12C (carbon-12, ~99% abundant), 13C (carbon-13, ~1% abundant) and 14C (carbon-14). The number refers to the atomic mass; all carbon has 6 protons but the number of neutrons ranges from 6 to 8; 8 neutrons means the nucleus is unstable and so 14C is radioactive with a half-life of 5,730 years and is called ‘radiocarbon’. The normal concentration of 14C in atmospheric CO2 is very small: about one 14C atom for every 830,000,000,000 12C atoms! This is why you need a particle accelerator to count them by the technique of AMS.

This trapping process continues over about another 20 m and at ~ 85 m depth, the ‘close off depth’, all the channels have become bubbles and no further exchange with the atmosphere is possible. So, it can be seen that the air in the bubbles is younger than the ice that encloses it; in practice there is also a spread of ages and this differs somewhat for each gas species as they have different coefficients of diffusion which affects the speed that they can move through the firn layer.

It is possible to drill a blind hole, stopping at depths all the way from the surface to the close off depth, to plug that hole with an inflatable bladder, and to pump ‘firn air’ from the base of the hole to tanks at the surface. Large samples of old air (~ 500 L) can be collected in this way and the air comes from a narrow depth range.

This is because of density changes which produce layers in the firn that are less permeable than others and tend to suppress vertical movement of the air. These layers are normally produced seasonally. So, the objective is to obtain a series of firn air samples at about 13 levels from about 5 m depth down to the close off depth.

A number of different gas tanks and vessels will be filled at each level and will be sent to different laboratories for analysis.

But the firn air can also contain 14C that has originated not from the atmosphere but is produced in situ by cosmic rays, or more correctly by the energetic secondary particles that are produced when the primary cosmic ray loses its huge initial energy by collisions with gaseous nuclei in the atmosphere. On reaching the Earth’s surface, these secondary cosmic rays still have enough energy to split apart the O (oxygen) nuclei in the H2O (water) of which the ice is comprised. Some of these nuclear fragments contain 6 protons and 8 neutrons and so are 14C nuclei which quickly react to form 14CO, 14CO2 and 14CH4. We need to fully understand the fate of this in situ produced 14C for a number of reasons.

Saturday 4 May: Greetings from Goose Bay... with Canadian ice cream

Got up at 04:30 to meet others in hotel lobby at 05:00. Made our way by car to ANG (Air National Guards) Stratton Base where we arrived ~ 06:00.

Just like commercial airlines, there was checked-in and carry-on luggage, screening for weapons and liquids and electronic devices had to be turned off for take-off and landing. After checking in our luggage we waited until ~ 09:15 before boarding. The C130 took off about 09:30.

We landed again at Albany at ~ 10:20. Apparently there were problems with the hydraulics and it was necessary to change planes. We're still waiting to load at 12:00 as I write this. There is talk that the control tower at

Kangerlussuaq will be closed by the time we would arrive if our departure is delayed much longer, in which case we may not leave here today.

But we did. The plane left at ~ 13:15 and we landed at

Goose Bay, Labrador, at ~16:45. The ANG pilots are very skilled and they touch down very softly. Goose Bay is approximately half way to Kangerlussuaq and the landing strip was originally used for refuelling stops when trans-Atlantic flights first began between the USA and Europe.

That was also the reason why we stopped: the plane was heavily laden and we were burning fuel: every seat in the C130 was taken (35 passengers and about 8 crew) and the rest of the hold was filled with pallets of cargo. Flying in these C130s is quite an experience: the passengers sit in webbed seats in the front of the hold, just behind the cockpit.

There are seats against the fuselage and seats either side of the centre: four rows, with the passengers facing each other. Take off is impressive; the props are wound up with the brakes on and when they are released the plane springs forward and gets airborne quickly. Ear plugs or mufflers are essential: the four propellers make a lot of noise. Noise cancelling earphones were prevalent. The ‘cabin’ temperature is controlled by one of the crew and was not too bad for most of the flight. In the back of the hold are the pallets of cargo.

I congratulated myself on finding a chair at the front on the right centre that didn’t have anyone facing me so I could stretch out my legs. That was until someone pointed out that the stainless steel device next to me that looked like a garbage bin was I fact the urinal; there was a curtain that could pulled around to give some privacy. Fortunately no one used it!

The light was fairly dim when we landed. Goose Bay airport is not a very prepossessing place, but we were warmly greeted in the waiting room with Canadian ice creams (this is a tradition), warm drinks and comfortable leather arm chairs. Refuelling didn’t take too long and we were airborne again at Although there are windows on the C130s they are small and you have to leave your seat to look through them; the few times I did so there wasn’t much to see other than clouds below.

It is apparently possible to visit the cockpit but I didn’t bother on this flight; I’ll wait for the flight from Kangerlussuaq to Summit.

Refuelling as done quickly and we were back in the air at ~19:30. The remainder of the flight passed the same way: reading, listening to music and dozing. We landed at Kanger 3 ½ hours later at 01:00 or 23:00 local time; Kanger is 2 hours ahead of New York (Albany) time and is exactly 12 hours later than Sydney time. It was quite dark and cold, and we lined up on the tarmac outside the bus for an immigration official to inspect our passports and stamp them.

As I was the second last out of the plane I was quite glad to get inside the bus! Then there was a short journey to KISS: Kangerlussuaq International Scientific Support. We were ushered into the kitchen where there was a goodly meal of rice, prawn curry and a chicken dish awaiting us, which we wolfed down. We have a briefing about KISS and tomorrow’s schedule, were given our room keys and internet access codes. By this time our luggage had been dumped outside. After retrieving bags and getting organised for an early start tomorrow it was well past midnight.

Although in need of strong drink I couldn’t be bothered seeking out the bar which was allegedly open somewhere in Kanger until 3 am and crashed out.

Friday 3 May: Andrew arrives in Rochester

Woke up at 08:30. While Vas packed, I went for a walk up Cobb Hill where the local emergency reservoir (circa 1908) is to be found. Good views over Rochester with Lake Ontario beyond. Interesting geology: Cobb Hill is part of a complex moraine left behind following the retreat of the Labrador Ice Sheet at the termination of the last Glacial Period. The weather was excellent: warm and sunny with no wind.

That afternoon we went to University of Rochester where I saw Vas’s labs and met some of his students.

Left Rochester ~ 19:30 by car, arriving in Albany about 23:00. Checked into a hotel and crashed out.

Thursday 2nd May: The adventure begins!

Departed Sydney UA flight L946LJ to Rochester via San Francisco and Washington Dulles.

I had just under two hours in transit at San Francisco. This was a potential problem: the luggage was checked all the way through to Rochester, however as San Francisco was the first port of entry into the USA I had to clear immigration and customs.

Lengthy queues caused some concern! The one hour in transit in Dulles also left little time for the ground staff to move the luggage between the planes. Without my cold weather gear I would not be going to Greenland. Despite my concerns, I arrived in Rochester at 23:00 along with my luggage!

I was met by Vas Petrenko, the expedition leader, and stayed at Vas’s house overnight. I had a much needed shower and sleep after a 21 hour trip.