The popularity of smartphones continues to grow with the availability of an ever-growing range of applications. The app, Radioactivity Counter, is designed to measure a person’s exposure to radiation.

|

It claims to accurately detect the dose in the radiation unit microGray per hour (μGy/h) using the phones in-built camera, which is not only sensitive to visible light, but to higher energy gamma photons.

Alison Flynn and her ANSTO colleagues tested the performance of the app against its claims using two different phones: the Apple iPhone 4S and the Samsung Galaxy S2. The phones were tested using ANSTO’s Instrument Calibration Facility and the results showed the application is indeed able to measure exposure to radiation.

It delivers a linear response to changes in dose, meaning the device can be accurately calibrated to reliably determine the potential dose rate to which a person is exposed.

| Alison Flynn, Andrew Wotherspoon, Stewart Gill, Anthony Overton, Mark Reinhard ANSTO |

How to detect radiation in a metal-oxide-semiconductor chip

The increasing popularity of smartphones and portable devices, and the availability of a wide range of downloadable applications (or ‘apps’) for such technology, continues to introduce new functionality and utility. Radiation detector apps are now available commercially for both Apple and Android devices.

These apps utilise the ionising radiation sensitivity of on board silicon-based complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) cameras to monitor radiation levels in the surroundings.

The CMOS devices

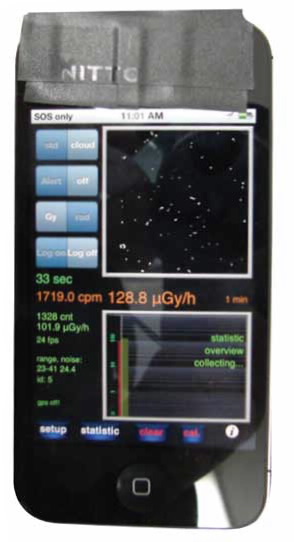

The application of black electrical tape over the camera lens eliminates the visible light response allowing the penetrating gammarays and/or x-rays to be observed. The radiation detector app uses the phone to record the number of times it detects an interaction and that number is converted into the dose received by the phone. This study aims to determine how well the application works as a dosimeter.

With the application of the black tape, the device will be sensitive to gammarays and x-rays but will be unable to detect beta or alpha particles or neutrons.

|

This shows the display the iPhone with the app running and a 137Cs source placed behind the phone. The top right panel shows the response of the camera, with dots representing where gamma-ray photons have interacted in the CMOS chip. |

Testing procedure

In order to accurately work as a dosimeter the phone must have a linear response to the dose rates which it is exposed to. This means that the device can be accurately calibrated and that its dose determinations will be reproducible. Also the device should give the same result regardless of the orientation in which it is being held i.e. its angular dependence.

Two smartphone devices were evaluated using the Instrument Calibration Facility (ICF) at ANSTO. The ICF consists of a range of 137Cs sources and a movable platform.

Each source can achieve a range of different dose rates, once the operator has entered the desired dose rate the position of that dose rate is calculated and the platform moves to the desired distance from the source.

For a range of dose rates from 1 to 349,796 microsieverts per hour (μSv/h) (for x-ray and gamma rays Gy and Sv are equivalent) each phone was used to acquire five one minute counts for each dose rate.

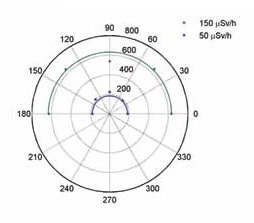

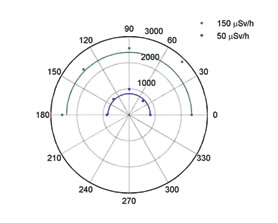

For a constant dose rate the phones were rotated to determine the angular dependence.

Results

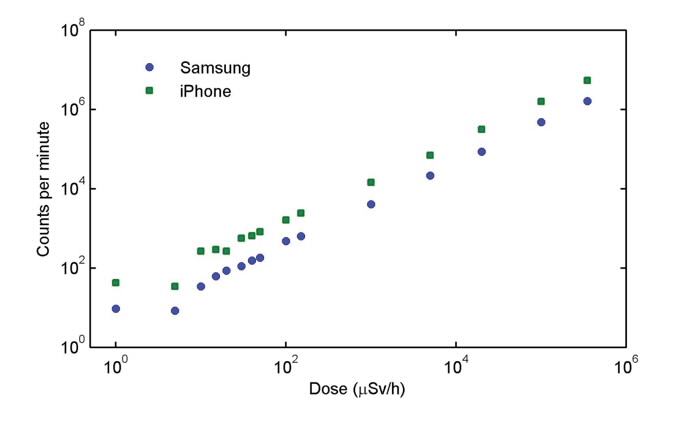

For both phones the counts per minute recorded were directly proportional to the dose rate for dose rates above 20 μGy/h for the Samsung and 30 μGy/h for the iPhone with results shown in Fig. 2. The average dose rate on a long haul flight is around 7 μGy/h.

The poorer performance of the iPhone is attributed to the fact that only the front camera could be used; there is a possibility that light from the display of the screen could be detected in the camera through the top layer of glass.

|

| Figure 2: The counts per minute recorded with both phones. A linear relationship shows that by observing the number of counts recorded the dose can be determined. |

The dose rate at which the phones can accurately calculate the dose rate is equivalent to 0.2 Sv if exposed for an entire year, this is 200 times higher than the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA) dose limit for the general public of 1 mSv [1].

In a situation where this level of exposure is only for a short period of time this dose should be avoided if possible, but has no long term consequences. To reach their yearly limit a person would have to be exposed to 20 μGy/h for approximately 50 hours.

The app would allow a person to vacate to a location where they would receive a lower dose.

These results show that the devices can accurately determine the dose rate which a person is exposed to and that the phone is sensitive enough to detect radiation at levels which are significant in a radiological event.

|  |

| Figure 3: The angular response of the Samsung Galaxy S2 smartphone at two different dose rates, 50 μSv/h and 150 μSv/h.The dots represent the number of counts recorded by the phone at different orientation angles. | Figure 4: The angular response of the iPhone 4S smartphone at two different dose rates, 50 μSv/h and 150 μSv/h. The dots represent the number of counts recorded by the phone at different orientation angles. |

Reference

- ICRP. (1990). 1990 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. CRP Publication, 60(ICRP 21), 1-3.

Published: 16/06/2014