Our history books say links between Eastern and Western cultures were established 2000 years ago. Thanks to new isotopic techniques a team of nuclear scientists now believe we should push that date back to 4000 years.

Nuclear techniques are finding increasing utility in telling us who we are and where we have come from. Our research is shedding new light on early cultural connectivity across Eurasia by investigating sites in north-west China.

Separate systems of agriculture emerged independently in eastern and western Asia around 8000 -10,000 years ago.

In the east, incipient agriculture centred on cultivating millet and rice, while in the west, it centred on wheat and barley.

We are applying isotopic methods and atom mass-spectrometry with radiocarbon dating to archaeological remains from Bronze Age sites in northern China in order to better understand cereal cultivation, animal husbandry and bronze metal-work technology.

Civilisations in the East and West

Some of the first significant human innovations in agriculture and technology were developed between 10,000 and 3000 years ago. This was when people learned to select and improve the characteristics of crops, to domesticate animals and to produce new tools using metallurgy.

These were the essential elements that enabled sedentary and then village life, and allowed societies to expand specialisations that produced writing, literature, music, politics, culture and innovation – essential ingredients that elevated achievement and improved life outcomes for humans generally. Of course most societies are still on this journey.

Archaeology and prehistoric records tell us that two of the greatest and earliest centres of urban life were in the East (in what is now recognised as part of China) and the West, centred on the Levant (including modern-day Syria, Lebanon and Jordan).

Agriculture emerged independently in both regions around 10,000 to 8000 years ago. In the Levant it was centred on wheat and barley, while in China it centred on millet and rice. Metal-work technology also represents a significant cultural advance, and it is sites in western Asia that yield the oldest metal tools.

There, metal tools were made from copper, until the technology of making bronze, by adding small amounts of tin and/or arsenic to copper in hotter smelting systems, was developed.

Links between eastern and western civilisations were well established 2000 years ago. By this time clear trading routes were established between the two major cities of the day namely, Baghdad in the west and Xi’an in the east with many staging posts between the two cities.

This route became known as the Silk Road, deriving its name from the precious silken products made from a secret process in China that drove westerners mad with desire for the precious fabric.

The power of isotopic methods is shining new light on this view of history, and in recent years has demonstrated that the Silk Road has also been an Agriculture Road, a Bronze Road and more, and has been an East-West networking route for more than 4000 years.

|

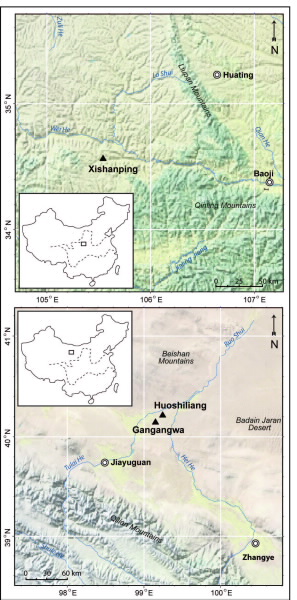

| Fig 1. Location of field sites in the Guanzhong Basin and Hexi Corridor of northern and north-western China. The upper map shows the location of Xishanping, the lower map shows the location of Huoshiliang and Gangangwa. |

Ancient bronze in the Hexi Corridor

Scientists at ANSTO and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Xi’an and Beijing have been examining bronze metal-work remains at Huoshiliang site in the Hexi Corridor of north-west China (Fig. 1 and 2 - Refer to the image library below).

The remains have now been dated in context to a bit before 4000 years ago placing Huoshiliang amongst the oldest bronze sites in China. Was this bronze imported with other western technologies such as wheat farming, or was it developed independently in China? Well, the ages from Huoshiliang are younger than those from Syria and suggest the technology may in fact have been imported from the West.

Can we determine if the bronze at Huoshiliang was made locally or carried east with the technology? The answer is yes we can and nuclear techniques are the key for doing this.

|

| Fig 2. Photograph showing the surface scatter of cultural remains at Huoshiliang site. Inset shows pottery fragments in situ at the surface scatter. |

The bronze contains a large number of trace elements, such as lead and strontium. These metals have isotope mixes which are specific to individual ore bodies and arise from differences in the age and past geochemical processes at each ore site.

These isotopic signatures carry through to the final metal objects.

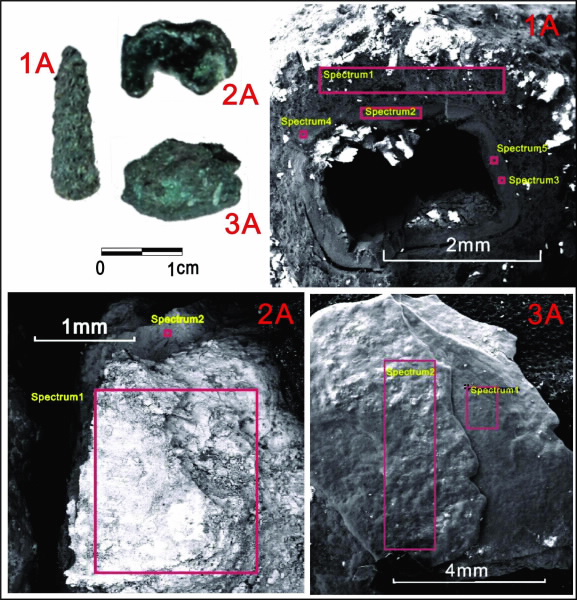

We have measured the abundance of a range of lead and strontium isotopes from bronze slag, bronze tools and copper ore samples collected at Huoshiliang (Fig. 3), and from ore samples from a modern day copper mine at Baishantang, located about 50 km to the north-west [1]. These measurements were taken using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) which is capable of determining minute concentrations of metals.

Most of the site’s samples produce isotope signatures that are statistically identical to the mine’s samples, indicating the bronze was manufactured locally.

One sample from Huoshiliang has a different isotope mix, and thus originated from a place at present unknown.

|

| Fig 3. Three artefact pieces from Huoshiliang shown under a scanning electron microscope. The red rectangles indicate locations targeted for energy dispersive X-ray (EDS) analysis [1]. |

Western domesticates in ancient China

In order to better understand the antiquity of western domesticates in China, botanical remains from Huoshiliang, Gangangwa and Xishanping in north-west China (Fig. 1) are being examined.

Much evidence about early agricultural practices is in the form of charred seeds, and at these sites millet dominates. Rice, wheat and barley are also present.

At Xishanping, wheat remains have been radiocarbon dated, using ANSTO’s STAR accelerator, to ca. 4650 calibrated years before present. This is the oldest confirmed wheat in eastern Asia, and is firm evidence that there was exchange between the West and East more than 2000 years before the Silk Road route, as is traditionally recognised in the history books.

|

| John Dodson, Xiaoqiang Li and Xinying Zhou discussing sampling in the field. |

Dietary clues from skeletal remains

Apart from seeds, abundant pottery, metal and stone artefacts and bone have been recovered from the ancient agro-pastoral sites of Huoshiliang and Gangangwa, in the Hexi Corridor.

At ANSTO, we are applying sophisticated treatments to extract bone protein and determining its integrity in order to provide reliable radiocarbon ages on bone from human, cattle, sheep/goat, rat, pig, dog and cat. To date, the ages of the bone fall around 4000 years ago.

Stable isotope ratios of carbon and nitrogen, measured on anelemental analyser – isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA-IRMS), are giving clues about the diets of the inhabitants of these ancient sites.

Stable carbon isotope ratios enriched in the heavier isotope (13C) indicate millet was the principle component of human diets as well as some of the domestic animals, while herded animals yield carbon and nitrogen stable isotopic signatures suggesting grazing was well beyond the agricultural areas [2].

Further work at these sites will contribute to knowledge on the history of domestication, particularly of pig, sheep and cattle, to allow us to learn more about our ancient beginnings.

Authors

Pia Atahan1, Fiona Bertuch1, John Dodson1 and Xiaoqiang Li 2

1ANSTO, 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Science, Beijing, China

References

- Dodson, J., Li, X., Ji, M., Zhao, K., Zhou, X., Levchenko, V., (2009). Early Bronze in two Holocene archaeological sites in Gansu, NW China. Quaternary Research 72, 309-314.

- Atahan, P., Dodson, J., Li, X., Zhou, X., Hu, S., Bertuch, F., Sun, N. 2011. Subsistence and the isotopic signature of herding in the Bronze Age Hexi Corridor, NW Gansu, China. Journal of Archaeological Science, 38(7), 1747-1753

Published: 19/03/2011